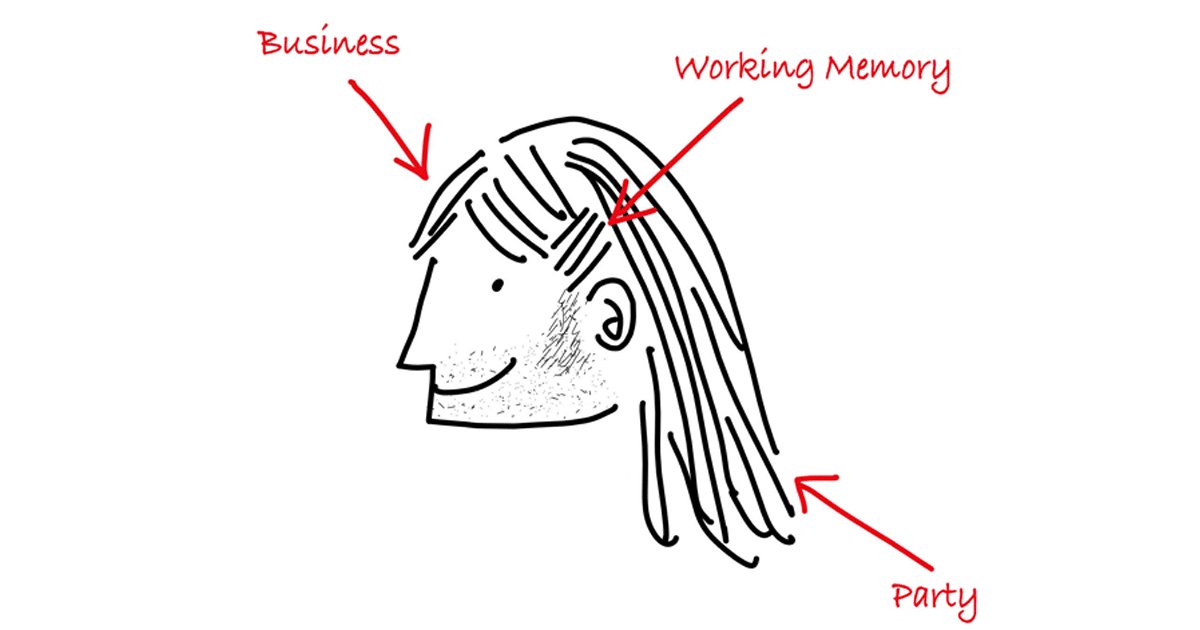

Personal tastes aside, this was probably a tough cut for stylists to achieve (and a tough style for me to draw, obviously!). How do you take short hair in front and long hair in back and create a style that looks cohesive? No doubt, it was hard work for even the most experienced stylist.

At The Possibilities Clinic, I talk with parents and students about memory a lot. I draw a lot, too—on the newly installed whiteboards—to try and illustrate abstract concepts from neuroscience, like how memory works. When I speak with students about memory, I often hear this: “I have a bad memory,” or “I studied hard, but I completely blanked out on the test!” My next question is usually, “Well, how exactly did you study?” The answers tend to have similar themes: highlighting the textbook, reading notes repeatedly, writing out notes over and over, and ‘pulling all-nighters’ to cram for exams the very next day. Do these techniques work? Usually not.

Fergus Craik and Robert Lockhart, psychology professors from the University of Toronto, would say that these approaches fail because information isn’t being processed deeply. Their perspective, known as levels of processing, has been studied for almost 50 years—and the basic principles continue to hold true! Information that is processed deeply will be remembered better than information that is processed at a shallow level.

So, what makes information processing shallow or deep? Well, the simplest answer is how well the information is integrated into something meaningful you already know. When you’re introduced to someone at a party, you might hear the name once—and say it once—but then forget it a few seconds later. Craik and Lockhart would argue that you processed the name at a shallow level because you didn’t do much with it. But if you hear a name, and combine it with something you already know, then you’ve processed the name more deeply and are more likely to remember it.

If you meet “Duncan” for the first time, and think of a co-worker named Duncan, you’ve integrated present information with past knowledge that is meaningful, and “Duncan” is more likely to stick. But this approach may not be foolproof; you probably have many coworkers, and you might end up calling Duncan, “Dan,” who’s the guy in the cubicle next to you.

Memory strategies, also called mnemonics, could help you process the information even more deeply. For example, if you picture Duncan with a cup of coffee and a gigantic donut covered with neon-blue icing that is dripping into his coffee cup—because Duncan is “Dunkin’ Donuts”— you’re now more likely to remember his name and refrain from calling him Dan or Don or anything else. Creating strange, funny, or unlikely images is a form of deep processing that can help make information harder to forget and easier to retrieve days, weeks, and even years later.

Students are more active in their studying—and processing information more deeply—when they relate what they are learning now to what they already know. But just understanding concepts based on previous knowledge—of biology or chemistry, for example—might not be deep enough when it comes to remembering at test time. If a theory has five principles, a student who understands the principles based on prior knowledge is ahead of the game. But a student who understands the material and has some fun building humorous, strange or unlikely images to tie the principles together has an even better shot at a glowing grade.

Speaking of images, what’s the deal with the mullet? Connecting information up front with information further back—specifically from your long-term memory—can be a tough task when studying, especially for students with ADHD. Students with ADHD are less likely to use effective memory strategies and more likely to forget information than students without ADHD. One reason for this difference might be related to weak working memory. Working memory is responsible for holding multiple pieces of information in mind—all at once—and integrating those pieces without dropping any to solve a problem or reach a goal. When it comes to processing anything, working memory is kind of like that mullet mid-section—integrating front and back—present information with past knowledge—to create a cohesive and memorable story.

And like the mullet, when relatively “boring” academic material in the present (aka business in front) is paired with fun and absurd images culled from a mishmash of past experiences (aka party in back), the outcome is striking—and memorable!

In ADHD, working memory is often weak, which can disrupt deep processing. But here’s the good news. Research shows that memory strategies, when taught explicitly to students with ADHD, can boost remembering. Furthermore, visual memory strategies can be effective for students with all kinds of learning styles. Sure, deep processing is hard work for working memory, and using strategies takes practice. But mnemonics can be fun, too, and a great advantage when there’s more in memory to mull over at test time.